Borges and I

A Fiction

“... la literatura no es otra cosa que un sueño dirigido.” — Borges

(Previously published in Hispanic Journal, vol. 45, no. 1, 2024, pp.125-34.)

I

Anoche, soñé con Borges—that is to say, last night I dreamt of Borges. But the Spanish con feels much more exact in conveying the feeling that I met with him in the dream; that he dreamt with me, and I with him.

He greeted me as an old colleague, as though we were collaborators, but I knew (or thought I knew) this was a fiction of the dream. I told him of the immense influence of his work on my own, that I imitate his style in most of my writing, that if he would just read one of my stories and help me craft it just right... He smiled, confused, then spoke with perfect English, fluctuating in dialectical variance from New England to the language of Yeats and Bernard Shaw: “you know, I didn’t recognize you until I heard your voice. When I first found you in my youth, so many years ago, you came to me as an old man. You had stories to tell, but you hardly shared anything. And when you did, it was always quite brilliant. And yet, no matter how hard I tried to find you in these dreams you would visit only infrequently. And now that I approach the end of my life, I want to cease being Borges as you seem to cease being you. It’s as though you were growing younger, into the self that had yet to write a single thing in your life. A return to the child as the father of the man.”

He continued, “I find it completely perplexing that, no matter the age or life experience, one never quite figures out what exactly happens in dreams, particularly those that pass as one interconnected night and day.” He paused. “So you brought a story with you, then? And you’ll let me read it?”

He spoke as if from the dust of the earth, as though from the dead to the living; I had no idea what he meant. Eventually, I looked down at my hands and saw a finished manuscript marked in my own pen. The words appeared blurred and illegible. A dementiated memory—there, just beyond the reach of my mind. I gave him the pages. He leafed them through and smiled, “very curious. Of course this is a good one. Much like our meetings here, I suppose.” Then he whispered to himself, “un Borges joven, que maravilla.”

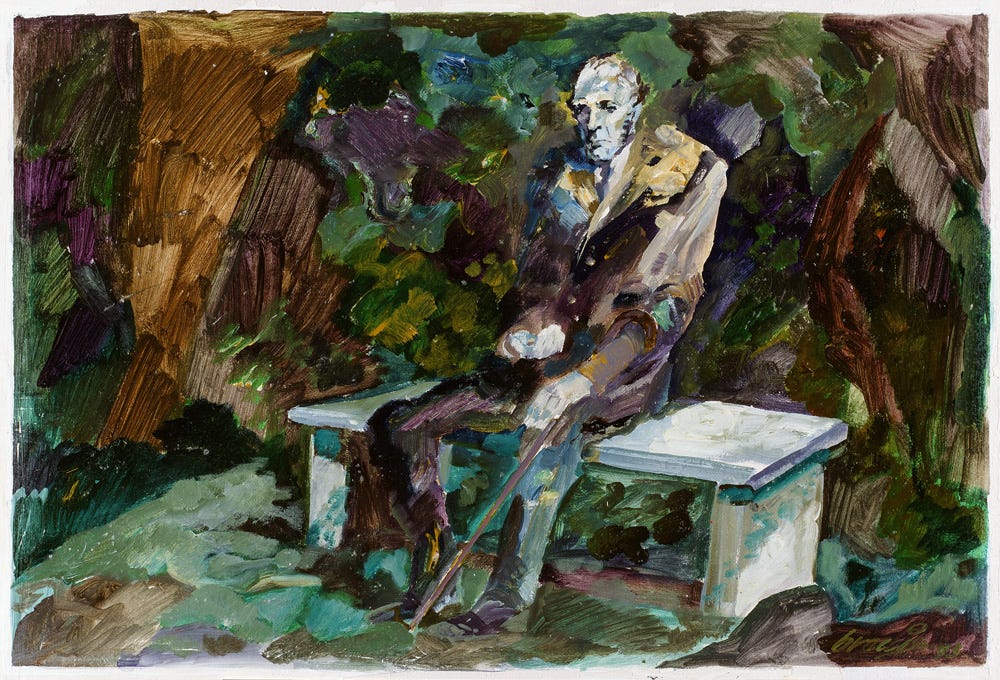

We entered his home together—an uncanny mix of Japanese minka and stately southern Argentine aldea. Though in his old age, thinned white hair and all, he was neither blind nor brittle. He stood straight and handsome, more closely reflecting his writing than his frame as I had seen in photographs. He lived on a large plot of land with cattle and wild forest that ran verdant into the horizon, with the sun glimmering in a constant setting and dawning. We ate together: thick cuts of smokey beef, charred and salted from the land. We sat beside rows of books and a Marrakeshian hourglass filled infinitely with sand that never moved, and we spoke of la pampa, los gauchos, o sertão and many things I no longer remember, except one.

As with any dream, no combination of words or symbols could properly convey the sensation of thinking this was the first of many encounters but feeling we had spoken before—though never of the soul (his keen intent on understanding my beliefs spoke to that lack). I shared with him freely, telling of my own experiences with the Divine. He stared at me as we talked, as though reading a novel. At one point he stood to leave the room. When he returned, he carried with him a pen, wrapped in gold and azabache, and two sets of paper: a fresh stack, and an old well-worked set of pages covered in notes. He sat and separated the piles and wrote.

As he carved his pen into the paper, he would look back and forth between me and the pages, painting with words, asking me (with both his mouth and his hands) to continue explaining my beliefs. After some hours he stopped and gazed through the window to the goldgreen plain. “You know,” he said, his eyes fixed on his land, “I visited Utah, and Brigham Young University a few years ago, in 1972. Very peculiar place. I would like to go back and teach a semester. I cried when I first read of your people and their history, crossing the Mississippi on ice when forced to leave their city, what was it called?”

“Nauvoo.”

“Yes, that’s right. Yes, religious people, like yourself I suppose, are amazing: full of mazes, very real mazes. I’ve passed through some here in this world, some in the other.” He continued to write.

Because I spoke in truth, he reciprocated, always gazing out the window. He told me of his mystical experiences. He called them the minotaurs of his own mazes. He spoke of many more things, beautiful things relating to the infinite and the Divine, but my mortal mind was unprepared to hold the pearls he unveiled that night. Most of his words now elude me, but the feelings remain. Of the things I remember he told me not to share, so I won’t write them here—but, in many ways, they confirmed much of my own beliefs.

He penned away as his eyes drifted between the fields and the pages. Eventually I asked what he wrote. He looked me in the eye, “ever since we met, so many years ago, I’ve had a story in mind for you: you, one of my most elusive characters. To be honest, only when we first met did I ever consider you ‘religious,’ but never after that. My mistake, I suppose. But it makes sense to a degree. Whenever we meet you seem so real, and maybe that’s your religious nature. To be human, of course, is to be religious. We can’t help but tie ourselves back to those people or things that gave us life, or at least attempt to—religare, to tie back, to bind back. I certainly do so in my writing, attempting to tie myself back into my own literary progenitors. Hopefully I will be lost in their voices when I die.”

His eyes shone a glint of light, “of course, you’re the protagonist of the story. It’s a fantastic story, very simple: it’s the narration of our meetings here in dreams, much like this cuento you brought for me today, or tonight, perhaps both.” He pointed to the manuscript I brought unawares. “But in my story, which I’ve been working on for some time, I always get caught up at one specific part which I’ve never been able to unravel. Probably—I’m now realizing—because I don’t know you as I should. But these things you’ve told me, things beyond the eyes alone, it opened that story up again, and I’m remembering it now.” He looked at the last page. “Now I know how it ends, or how I might dream that it would end. And, as you taught me long ago, you have to write these things down before they dry up in your memory.”

The thought of being a character in one of Borges’ stories, a projection, a fiction of his mind, didn’t surprise me—that was always one of my favorite tropes of his. But when you experience it as something real, it simultaneously fills you with near infinite joy and endless terror. He saw this play out on my face and assured me I would read the story, but that it would take some time to finish writing.

The sun shifted from dawning to setting, and my mouth grew dry and without words. I edged to the threshold of his home and heard the whispers of my awakening. He walked to me and touched my cheek and stared into my eyes. He looked into me as a grandfather driving hope into his grandson and said, “what you’ve given me over the years, I’ve never properly thanked you.”

Again, I didn’t know how to respond, nor did I understand. He kissed my cheek and told me to come back the next day. He said he wanted to properly express his gratitude for what he called my work. He then made sure I left my manuscript, which seemed less important as the dream went on. He picked it up and skimmed it through again (for the life of me I can’t remember anything on those pages except the familiarity of my own handwriting). He smiled as he read, the exact inevitable smile I give when reading his work.

I woke up.

I couldn’t go back to sleep. I needed to write down the dream. But I only wrote moments and phrases until my wife and little ones stirred with the rising sun. Normally, I would take a dream like this and blend it with narrative for my own fictions. But I’m afraid to explore this one, though I’ve had no new ideas for stories in some time. The dream continues to play in my mind on repeat. It rings as though a message with some significance. I have no idea what it means.

II

I dreamt with Borges again—only now the word dream as I write it out on paper reads as engaño: a deception, a fiction hardly conveying the reality of his visit. But a dream it was, as real as the hand that records these words.

We met again at his home—Borges and I—there in his library. The bookshelves ran endless, more than the previous dream, winding and twisting. The books painted for me a portrait of Borges I knew few had experienced before. At the ends of the vast library sat opposing hearths with large mirrors hanging above the mantles, reflecting one another into the infinite. He told me of the time he spends in those mirrors, wandering the layers of infinity and reading stories one could never find in the waking world.

He drew a fire on the eastern mantle and we spoke for three days. The pinewood burned unimpeded. The light of the flame rose in steady rhythms as Borges took two small stacks of paper from an end table. He combined new pages with the old ones from other dreams and fanned them through until the beige color of each leaf sang in unison.

“I’ve spent a lot of time,” he said, “learning from you over the years, but never about you, as I’ve done with others before. But that all changed since our last encounter. I’ve made good work since, learning about you and realizing a few things. It’s helped me finish, or nearly finish my fiction.”

He proceeded to tell me—or rather, to read to me—of myself, making notes as he went along. He read from the taupe pages of things in my past, things I couldn’t remember (or didn’t want to remember), attempting to verify his writing against my lived experience (a gesture of politeness, I suppose, since to him I was only a projection of his mind). He spoke of things in the present, things I thought were only known to me: of my wife and children, of my dreams for them and worries. He spoke of things as though they were memories for him yet to be lived by me. He read of a new life and an old life that were one and the same. His words spoke with broad and indelible detail, forming a written mirror of the past and the present and the future. I did not say a word as he wrote and read, and read and wrote.

He continued working the pages with regal craft, skimming through, marking passages, crossing others off and said, “our previous conversation was most useful in getting to these details here on your beliefs. I was surprised.” He pointed to a few pages holding one dense, unbroken paragraph. “As you know, I wouldn’t have been able to write these passages without that conversation. And now that I have these details, I don’t think I need them anymore.” He took a red pen (these are the colors only ever known in dreams) and began to cross out the entire passage, page by page. With large maroon strokes he said, “these things were all necessary for what is to come, for what will be written in the end—but I don’t need them anymore.” He paused and looked out the large window, “now that’s something I haven’t seen for quite some time.” The framed glass revealed the pour of a brilliant white against evergreens and the gentle sun. The silent cold of falling snow filled the room.

He continued editing through his pages, infrequently asking for my approbation. I didn’t respond; I couldn’t deny a word he read. The way he worded my history felt much more real than anything I could remember. His words painted a scene for me of my lived reality, one that was, until that moment, impossible to witness. The words obliged me to behold my life as if I were another; and, even in the dream, I failed to process any meaning from it all. This went on well into the evening of the second day.

At the end of the last night, the sun broke from its setting and dawning and darkness crept in and he said, “now that that’s all settled, I’m a lot closer to this story’s end. But I’m not certain. Again, it’s your religious nature, much more real than I anticipated. I’ll need more time to write. I want you to read this story, it’s one of my better ones. It will be my way of thanking you for everything. Do you think you could come again, one more time? It seems you’re far less hesitant to meet than in years past.” He pointed to my lap. “But before you go, don’t forget to leave this last story of yours. I can’t thank you enough for your work, I really can’t. And to think you’d give me two in a row.”

I looked down at my hands to another set of papers and saw a second story written in my own pen. And, like the other, I couldn’t read it, however desperately I tried. I gave it to him as in the dream before and said I would find a way to return—unsure whether I lied or spoke in truth. He told me not to worry, that everything was taken care of. And as with the previous dream, he read through the manuscript and smiled the exact smile I give when I read his work.

Whether I woke from a dream or passed through a vision I do not know. I am afraid to make the distinction. All I can say is that I awoke (whatever that means now), with little to no rest, and wrote as much of these experiences as possible, despite my growing lack of creative output. My hands and lips slowed with cold as I wrote. I went to light the fireplace. As I looked outside, a quiet spring snow fell gently to the ground.

III

Night finally came and passed. I couldn’t sleep.

I spent the evening unsuccessfully lying down, searching for that moment of slippage from this world into the other. I longed to meet with Borges again, to read his gift to me, to see what it said of my life. I eventually sought relief from insomnia in the green velvet of my library chair. The sleeplessness—mixed with the yearning to meet again with Borges—forced me to his literary well.

I sat and tried to relax and drew from the depth of his work. I read in the light of the warm fire. I poured libations from his collected stories and read for the thousand-and-first time of Jaromir Hladík and that moment of infinity just before his execution—the gift God granted to finish his magnum opus. I read, drinking it in as if for the first time. I read other stories—two in particular that, somehow, I couldn’t remember reading until very recently: a curious encounter between the aged Borges and a younger version of himself, and a Bible seller who owned a book filled with pages as infinite as the sands of the sea. The words seemed to have written themselves and drew me in with their simplicity and the finite way they bound the infinite to something comprehensible. Yet, they gave no relief from the strains of my restless mind, nor did they bring me back into his presence.

All I could do was continue to read, my eyes blood-red, my mind driving deeper into wakefulness. The familiarity of these stories began to speak to me as an old friend, like reading a letter from a wiser version of myself. The cadence, the rhythms, the beats, the melodies of the fictions all sat unearthed before my eyes. These my favorite fictions. The fictions that brought me to Borges. I went from reading the stories to feeling them already penned in the fleshy tables of my heart, as though somehow Borges and I shared these stories together.

I wandered through these thoughts and feelings in the deep of night. The elusion of sleep wound my mind further into the world of narrative and creation and I determined to synthesize my dreams with fiction (as I had done many times before)—to examine the dreams as dreams (as fiction), and stare them straight in the eye.

I rose up to sit down at my desk. I moved messy stacks of books and papers to the side and gathered a pile of fresh pages. As I began to write, I heard the now familiar voice.

Again, whether I dreamt with Borges, or he came to me, I could never say—but there he was. And this time he came to me in my home. He brought me a story. My story.

I fed wood into the hearth under the western window and gave him a warm drink. As he sat, he handed me a ten-page manuscript: “This is for you, dear friend. It’s nothing fancy, but I want you to have it. Certainly, you know you inspired it. What do you think?”

I took the pages, warm from the solar blaze in his southern Argentina. It breathed in my hands with the same rhythms of my beating heart. I recognized the handwriting, eerily similar to my own. The black ink shown a vivacity in the curves of his f’s and m’s, just like mine. But when I went to read, I couldn’t. This time the words weren’t blurred as in the other dreams, but sealed. Though I could see them, they were not available to me, as though in a language I couldn’t read. Yet I knew the language, the language was my own.

Frustration and discomposure crept into my heart. If this was a dream, why couldn’t I read the story? I went again to read but was still unable. Before Borges could ask what was wrong, I attempted to distract him from my embarrassment. Though I now cared very little for my stories in past encounters, I asked: “what about my work, my stories? Won’t you tell me what you think of my fictions?”

His head tilted to the side and his brow bent inward, “yes, yes. But I suppose you remember them, don’t you?”

I searched my mind only to see white pages in my blurred handwriting: no discernible titles, words, edits, reds, narrative, story—only endless paper written by my own hand.

“But you do remember them, don’t you, surely it wasn’t that long ago?” His confused smile grew with the light of the hearthflame. “Well, certainly you must… But maybe,” he paused. “Now that’s curious.” He asked for his manuscript and pulled a pen from his suit coat and turned to the end of his story. After some time, he made significant edits, then handed it back to me. “There,” he said in bewilderment, “now it’s ready. Now it’s real.”

I didn’t understand and now felt more drawn to his confusion than the content of his story. “But won’t you give me feedback on my work?”

The perplexity of his smile burned into my memory, “you really don’t remember, do you? But certainly, you must? No? The story you brought me two dreams ago was quite clever—an encounter with a younger version of myself. I needed to fill in some of the specifics: streets, times, names, dates, etc. But you couldn’t have known that. I remembered the dream on the banks of the river Charles, in New England—the cold reminded me of the distant stream of the Rhône. Look how much I enjoyed it.” He walked to my desk and picked up a wellworn book: Cuentos completos por Jorge Luis Borges. He gave no expression of awe or intrigue at reading his own work. When he read, I remembered these words, “—Todo esto es un milagro—alcanzó a decir—y lo milagroso da miedo. Quienes fueron testigos de la resurrección de Lázaro habrán quedado horrorizados.”

“Or surely you will remember your older fiction, a man condemned to death? As Dostoevsky? When you told me it came from your reading of The Idiot, I knew I had to see it. That was the first one you gave me when I was younger. It took a lot of convincing to get you to share it. You are in nearly every detail of that story. I changed the name to Jaromir, but that’s about it. The rest was yours.” He flipped through the book and read, and I remembered these words, “Una voz ubicua le dijo: ‘El tiempo de tu labor ha sido otorgado.’”

“And this from our last encounter. It’s not your best, but still quite good. And look,” he said, pointing, “here it is with a few others. Curious. It seems my time isn’t quite at an end, at least according to your world. But that’s odd.” He squinted his eyes. “For the first time in this world my vision is, well, it’s not exactly blurred as it is in the other world, but I can’t read the rest of these stories.” He pulled the text closer to his face and said “no, the words aren’t blurred, they are sealed. I can see them, but it’s as though this were a language I couldn’t read. Yet I know this language, it’s my own.” He paused, “can you read this for me?” I took the book and remembered the story, now seeing the title as though written on my own manuscript.

“El libro de arena,” I said.

“Yes,” Borges said. “El libro de arena, The Book of Sand. That’s a decent title: a Bible seller with an infinite book, with pages as numerous as the sands of the sea. It’s good, and apparently I’ll use it, like I do most of your work. Look here, come, now I can read.” And he smiled my smile as he read and I remembered these words, “Me acosté y no dormí… No mostré a nadie mi tesoro. A la dicha de poseerlo se agregó el terror de que lo robaran, y después el recelo de que no fuera verdaderamente infinito.”

But his smile faded into confusion. And the tides of time and mind shifted from him to me as he said in a blur, “you see, what’s most interesting about you—and I’m only seeing this now—is that you are a real believer. I think I see now—that’s what allows us to have these dreams. You believe quite literally in the Divine. This makes you so much more human than any fiction I could have invented. This was the part of the story that, until now, I didn’t understand. Because you’re not a dream; I didn’t invent you. You are here with me, really here, conmigo.” He handed me my book again (or rather his book), saying, “these are the stories you gave me here in my dreams, your stories; don’t you remember? But surely you must know?”

And I didn’t respond, or if I did, I don’t remember what I said. After that there is no memory. Because while for me this was the first of what seemed to be a series of dreams to come, for Borges, this was the last of the dreams we had already shared—that I have yet to dream. All this time, in my living ignorance, I had met with Borges in the flesh of dreams. His beginning was my end, and his end was my beginning. And before I could realize what was going on, before I had time to ask those questions one should never ask, nor hear the answers, the sun dawned. And there in the snowy light of day, underneath an azabache pen, sat ten well-worked pages on my desk. There was nothing else. All my books were back on the shelves, my pages of notes were nowhere to be found (I still can’t find them), only these papers. In a curved hand at the top of the first page, now singing the familiar songs of disquiet, read: “Borges and I.”

If you liked this, subscribe here for more:

Thank you, for this. I'm not sure yet how you contained furious and etching motion within a placid mirror's surface of fiction, but you have.

You are a dope human