Paraíso

A Fiction: An Homage to Machado de Assis

Cuando los jugadores se hayan ido, / cuando el tiempo los haya consumido / ciertamente no habrá cesado el rito. — Jorge Luis Borges, “Ajedrez”

Everyday Pedro Rubião de Alvarenga would make his way from Sterling Heights to Campus Martius and escape in the infinitude of chess. He would play one match a day: a total of 1,574 wins, and 23 resignations (all to the Grandmaster Mash Al-dú). Although his skill surpassed nearly any who crossed his path (save Mash Al-dú), no one knew his name nor cared to ask. The occasional poor care of his Queen constituted his only weakness, and whenever he lost her, the game waxed unbearably finite. He rested on Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, Easter Sunday (hardly anyone showed up those days) and March 30th, but could never remember why.

For a long time now, Rubião thought of his memory as the impressionist painting of a blind man. And now, near the end of his life, he sought to revive the colors and sharpen the lines. So on March 30th of the previous year, just before dawn, he decided to play against routine and left for the park. An unusually prolonged winter lingered over the area, and the morning drew in brisk strokes of grey and blue. Rubião caught the early bus (as usual), intending to study old matches before the regulars arrived, but found himself preceded by a silhouette. The sharp air outlined a well-dressed, foreign-looking man in the distance, seated at the tables. As Rubião approached in trepidation, the stranger stood. A subtle, disquieting feeling of remembering came over him, which he hoped to slip away into his wintered mind.

But the feeling wouldn’t leave. From below an untamed mustache, and above an overgrown beard sang: “Hello Rubião. Come, it’s been some time.”

The recursive familiarity sang a little louder, but Rubião stood deaf by choice. He decided instead to frame the man with an untraceable accent, ignoring any thought to consider just exactly how the man knew his name.

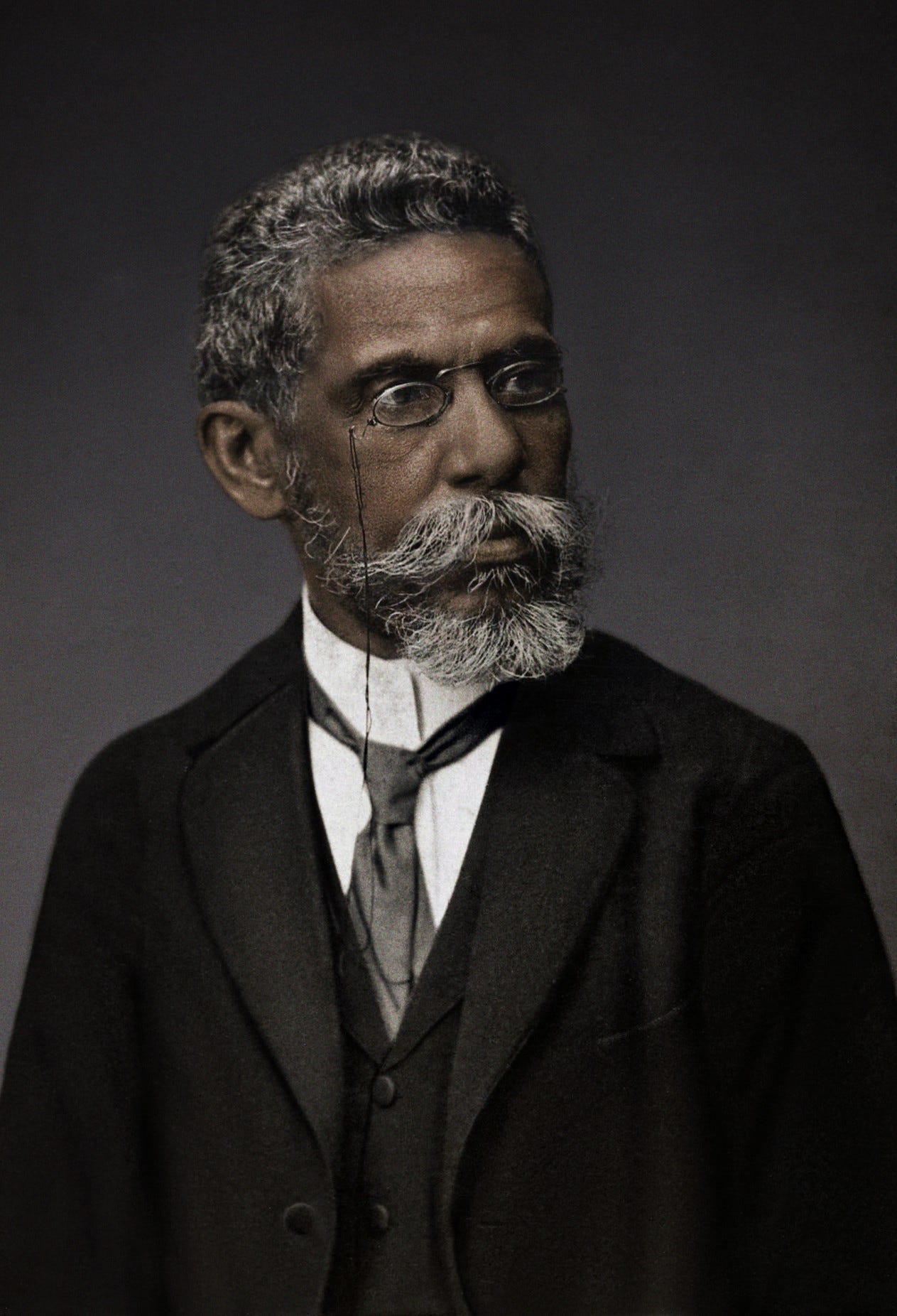

The stranger stood aged yet poised, wrinkled yet regal, his thick hair deceptively white against deep tones of skin. He dressed with an organized sense of self; his suit dated to the previous century yet seemed newer than those in vogue. A pair of thin spectacles hung on his larger nose and a curious apparatus rested on his wrist: a small black disc held by a dark band. Within the disc ran two thin gold needles operating at different speeds: the slower marched forward as the faster ran opposite.

“I know that device,” said Rubião, as if in a dream. “I read about it once in Deus Scriptor: The Kaluza-Klein Theory Revisited.” He paused. “Excuse me, but do I know you? Forgive me, my mind is leaving me, ou, tipo… Well, I can’t remember. Have we met before?”

A smile crossed the man’s mouth as he stated his name. But Rubião wasn’t listening, and feigned hardness of hearing: Mashado? Mashaldu? Mash Al-dú? Perhaps this was just one of those irritant Arabs who came to play with the Grandmaster: “Excuse me, did you say Mash Al-dú?”

“It is very good to see you, Rubião. Please, sit.” Machado replied, with eyes of forgiving.

As they took to the table, a thick daze glazed across Rubião’s eyes. The familiarity of the man now grew to an unignorable hum. But again, Rubião raised the flag of forgetfulness and invited him to a match, craving elusion among the false ivory. Machado agreed. They began.

Rubião opened with the king pawn. But in a matter of seconds he found himself in a quasi-transcendent checkmate after eight turns — his first true loss in one thousand and a half days—all without losing his Queen.

Astonished, Rubião muttered, “I once read about a similar sequence of moves in Pierre Menard’s translation of Livro da invenção liberal e arte do jogo do xadrez, I mean, sorry, his book on chess. But… this is precedent defeat.” Then he whispered, as if to himself, “it’s as though he knew my moves before I made them. How is this possible?” He studied the position, and looked up, unable to stare into Machado’s eyes. “How is this possible?”

“Well, didn’t you say you’ve read Menard’s work?” Machado said, locking his eyes onto Rubião with a smile.

The penetrative gaze pierced Rubião, even as he looked away abashed. Staring at his interlaced fingers, he responded in truth for the first time in many years, unaware of the change in conversation: “You know, I’m trying to remember an important date in my life, today’s date, in fact. I can’t remember its significance. I usually don’t play today. I mean, today, on this date, on March 30th. But I really don’t know why.”

“Is that so?”

“Yes. É assim,” he said, now unaware of their mutually natural drift into Portuguese. And as Machado spoke to him, Rubião fell into a sea of calm and wonder. And that calm grew in dissonance to the ongoing song of uncanny familiarity.

Not knowing what to say or do, Rubião offered another match, feeling full well that repeating a second loss was mathematically impossible. “Perhaps if we play again, it may revive my memory.”

“Distraction, yes. Yes. I must leave soon, but I can stay a little longer.”

They rearranged the pieces and commenced. But against the laws of nature and reality, the same moves repeated into checkmate beyond Rubião’s control, as though dictated by the Universe. A spark of humility caught flame as he now saw in this man metaphysical Genius. He pleaded with Machado, “how is this done?” Machado listened and took pity on his old friend. Before he left, he agreed to teach him, once a day, so long as Rubião would write down—with perfect precision—every move of every match. He told Rubião that this would help improve his game as it had for him many years ago, and perhaps his memory as well.

That night, as Rubião readied for bed, he found an empty notebook and determined to scratch out a few lines on both the day and the match. As he wrote, he wandered through a mindless labyrinth of thought, leading him in circles to that now overwhelming sense of remembering. The night drew cold and his head touched the desk, ankles crossed below. He found himself running through a library of endless stacks. He came to a stop. Drawn to a wall, first shelf, twenty-first book, he read the spine: “Sonia.” He turned at random to the 377th page and read silently: “Dad told me what happened, I don’t know how to forgive him. It’s only been two weeks. He came into my room as he did every night since she died. Tonight he brought a small wooden box mom made for him when they were first married in Rio. I can’t stop crying. She painted on it the word Paraíso, decorated with her usual floral embellishments and pink hues. He told me it all happened so fast, he showed me the diamond necklace and told me he wanted me to have it. I don’t ever want that thing near….” The text blurred into running, endless and tireless running. He stopped at another of the infinite shelves and opened a second book at random. He read of a mirror in which he saw himself writing a long and detailed entry regarding a rigorous match with Machado, appearing to end in stalemate. He dropped the book, only to run again, running and running and running away.

He hardly slept an hour. Unable to return to the world of dreams, he sat at his desk and, in the emptiness of the bare-white room, wrote more on the events of the day. Reexamining his notebook, he inserted fragmented memories and rounded out uneven thoughts on the eight-move defeat, scrapping to analyze each position. The aggregate sum of his experience with Machado now sat bound to the pages of the old notebook. As he read through what he wrote, he thought again on that now vertiginous familiarity of Machado.

The next day (as promised), Machado anticipated Rubião’s arrival, waiting patiently at the tables; signs of Spring still nowhere to be found. They greeted each other, engaged in simple conversation and started a quick match: a thirteen-move checkmate to Rubião. This pattern repeated for a week, a month, nearly a year as Rubião’s fascination with Machado grew and his yearning to learn from him turned insatiable. And Machado gave no indication of displeasure as the matches consumed greater lengths of time. In fact, the longer the matches, the more they spoke one with another—or rather, the more Rubião would speak to Machado. As they played, he would re-live memories (very superficially) with Machado. Certain moves would trigger unexpected moments from the past, which he shared unawares and without restraint — but never with names. He told of the birth of his daughter on one opening; of his wife’s voice with an elegant move of the Queen; of moving from Brazil to the US; of losing his wife. And Machado would sit, listening.

One evening, after a longer than usual match, Rubião finished his twenty-first notebook, articulating each moment of the loss in perfect precision. His writing now bloomed in detail and poetry with the repetition of days. He recorded each match with exquisite detail, mapping out even the seemingly meaningless moments: each breath taken by the two men, the angles of the hands guiding each piece on the board, the weathered texture of bishop, rook, knight, the atmospheric conditions, the frequency of the queen’s play, the gaze of both Machado and Rubião following the forecasted trajectory of individual strategy, the flora and fauna which, in retrospect, influenced the match, etc. With each written line, Machado grew from a lost memory into a presence just beyond his reach. Yet, despite their developing friendship, Rubião’s lack of recall pushed him to never ask who he was.

When he closed his writing, he looked up from his desk at the empty walls, as though staring into the mirror of his vacant memory. The unease at not remembering who Machado was, or the past beyond these matches, led him to write again: “After my match with Machado, I went home and Joana had put the children to bed. She was painting. So much of her rests in these strokes of paint. She came close to me, we kissed, and smiled. I dreamed that we lived in that painted paradisiacal scene of which we had always spoken.” And in closing the fiction, Rubião slept a full night for the first time in far too long.

Nearly a year now passed as if one day and one night. On March 29, the two met to play, as usual, enjoying the timely Spring weather. During the course of the match, Machado spoke abruptly: “Tell me about Joana.”

“What do you mean? How do you know that name?”

“You know what I mean. Tell me about her.”

“How do you know that name?”

“Well, for one, it is the name you mumble when you are about to lose.”

Rubião stared at his Queen’s next move, “Joana was my wife, she died almost 15 years ago.”

“What do you do to remember her?”

“I play chess.”

“Does it help?”

“Sometimes.” He paused and thought of her paintings. “She was lovely. She loved me, I think, that itself is lovely enough. I was a poor man, a coal miner, and she loved me still, coal dust and all. I used to tell her that I was a coal miner in order to search the earth for the diamonds God had saved for her. She asked every day if I found her diamonds, always in jest. We were married March 30th. Yes… That was a special day for us. Sonia was born on March 30th. Our Sonia, I wish I could see her again. I remember now, it all happened so long ago.” Tears formed in his melancholic eyes as he recalled the significance of the date unawares. His head hung heavy as the weight of his heart pulled him closer to the earth than he wanted. “As our marriage aged it became difficult to go back to the sweetness of the beginning. I was a very poor husband, I see that now, always working, always wanting, never giving. She had threatened to leave a few times, telling me it was dangerous for the children. It really shocked me when she actually left. She came back only because she pitied me; I suppose she thought she could save me. I began saving money. I thought if I could find her those diamonds, perhaps she would forgive me.” He broke down. The grief buried deep cracked ever so softly to the surface. And Machado listened patiently.

“I saved for a couple of years. I found a simple diamond necklace and purchased it on March 29th. The next day for our anniversary, I planned to give her the necklace, but she told me she wasn’t feeling well and needed to rest. I became upset, very upset. I regretted my actions as I made them. It was our anniversary. I began to shout and slam my fists. Through the noise she clasped her chest in pain, but I ignored her. She told me we might need to go to the hospital — Sonia begged me to take her to the hospital. You know, children see through the fighting, through the anger. They know when you’re wrong and it eats you. I told them both we had no money, which we didn’t, and that she just needed rest. I didn’t know. I just didn’t know… I woke up the next morning to her cold hands.… I just don’t know how I can face her in the afterlife...”

Machado said nothing, only listening. Rubião wiped his eyes and went back to the board. The remainder of the match, which drew on longer than any previous, sang silent. No words, just movement. The pieces favored Rubião, giving him an encouraging material advantage. The game slowly dwindled to Rubião’s king and rook against Machado’s king. Unsurprisingly, Machado took Rubião’s rook and finished the game in stalemate. Machado stood up, walked to Rubião and kissed his cheek. Without a word, he took from his wrist the black disc and placed it into Rubião’s hands.

“I can’t take that from you. What are you doing?”

He closed Rubião’s fingers over the device, put his hand on his cheek and kissed the other. After Rubião looked down at the gift, he went to thank Machado, but there was only wind. He ran to find him, but there was only sky. Unsure what to do, he rushed home to record the match. When he arrived, he tied the black disc to his wrist and wrote. Then, the inexplicable, the ineffable: those things which we feel but cannot say, which we know but cannot tell. And he wrote. In a moment approximating the infinite, the past connected to the present through pen and ink. He looked back into time and saw, with near perfectly clarity, each passing moment as the sum total of one whole. Juxtaposed to this intense joy sang an even deeper agony: for how does one re-live the most selfish moments of time? He felt, again, limitless grief and endless joy, all within the finite confines of pen and paper. He wrote and watched Joana, her white dress dancing on her youthful frame; her gentle hands held his, her piercing eyes and radiant joviality; the cry of their first baby, his unforeseen coetaneous death; the day Sonia was born, the day she ran away, the day she came back, the day he had seen her last. He counted and felt the eternal weight of the individual tears falling endlessly from Joana’s cheeks, all in rapid succession of absolute experience. He recalled all that was lost in a thousand breaths of life, arriving at the day’s match, written now in quasi perfection. Because as he went to write the stalemate, he wove in a fiction of triumph — a simple win between beloved friends. The pen drew heavy in his hand, and he went to bed, dreaming away the life left on his desk.

He arrived the next day at Campus Martius to meet Machado, but couldn’t find him. He waited for hours. Heavy disappointment set in from the ingrained habit of their meetings. Unaware of his speech, he told the usual opponents of Machado, but no one understood, except the Grandmaster Mash Al-dú. Though he spoke no Portuguese, he intuited something inexpressible in Rubião’s eyes and offered him a match in response. An unexpectedly complex game ensued, play by play, movement by movement, exactly mirroring the fictional match Rubião wrote in his notebook the previous night — particularly regarding his win with king and Queen vs. king. Amazement reverberated through the onlookers as they watched the dethroning of the Grandmaster. Mash Al-dú (who had never lost at Campus Martius) demanded a rematch, claiming fraud on the part of Rubião, who accepted for the subsequent day.

After the match, Rubião stayed, waiting for Machado, but he never came. Eventually, Rubião went home to record his victory and continue the pattern. But rather than write through the day’s match, he wrote the pending challenge with Mash Al-dú. After placing Machado’s black disc on his wrist, he wrote, in perfect detail, the moves he was to make as well as those of the Grandmaster. And writing through the foretold triumph circled back to writing again through his past, re-writing of Joana’s love and his care for her. He saw her into a long and healthy life; he sharpened their affection; he gave her the diamond necklace; he wrote of the many grandchildren that flooded their life with chaotic joy; he wrote Joana’s rich paintings onto the walls of his room, the paint compiling on top of paint in all directions, cupping him in the painterly vitality of Joana’s presence; he found himself with Machado, wondering how it was that he could have forgotten him; he wrote himself writing in his notebook as he lived the last days of his life. The timing syncopated into one whole: on the last pages of his book, the pen dried as he closed the record in tranquility, writing himself to sleep to awake in an infinite world of dreams.

•••

Sonia dreamt of her father for the third night in a row. She arrived at the old house, knocked and waited. No answer. She knocked again, eventually going through the back door. She called his name. No answer. She went to the fridge for a drink and into the living room. She turned to his desk and went deaf, soundless glass falling broken at her feet. His empty body, with pen in hand, sat collapsed on his desk blow her mother’s painting on the wall: “Paraíso.” Her lungs shrank. She removed the pen and grasped his cold hand, holding it to her cheek. Under his head sat an empty notebook. She searched for his watch to read a time of death (at least the time she found him), but his arms were bare. She kissed his cheek, looked up at her mother’s painting, and wept.

If you liked this, subscribe here for future stories:

*An Homage to Machado de Assis