The Currency of Attention; The Divinity of Perspectival Painting

“Después reflexioné que todas las cosas le suceden a uno precisamente, precisamente ahora” — Jorge Luis Borges

In English, the verb most commonly associated with the noun “attention” is monetary: to pay. We “pay attention” when a movie gets interesting; we “pay attention” to a lecture in preparation for an exam; a loving parent “pays attention” to her daughter after a hard day at school, etc. Thus, in English, we speak of attention as an asset — limited, liquid, expendable — and that’s precisely what it is. Every day we wake up with a replenished account of attention, reflected in the hours of the day. We constantly spend/exchange (or waste) this asset for something more fixed: in the examples above, the experience of an entertaining movie scene, the right answers on a test, or a real relationship with your daughter. In fact, when you pull back the layers, you come to realize that of all the things you think you “own,” there is only one that is truly yours, there is only one thing you or I can truly spend: attention.

Attention constitutes the singular expendable asset available to mankind. For example: money, the most universally recognized form of “capital” is not capital, but a representation of capital, i.e. attention.[1] Money is a fiction (even if backed by military prowess) that tells a superficial story of how one spent what was truly his or hers (attention). If you spend your attention on skills valued by society — writing, let’s say — eventually that attention, if focused in the right way, will likely compound into something worth reading (spending one’s attention on) in exchange for money. But the money from this transaction is not the value, it is a representation of the value already spent. In this sense, we don’t own money[2] (not to mention inflation, Executive Order 6102, etc.); money is a tangential signifier for how you or I (or someone else: ancestors, founders of the company you work for, etc.) spent our attention. Attention is the only thing anyone truly “owns,” yours to use in any circumstance and at every moment — for your betterment or detriment. And to focus your attention on the right things is infinite power; to focus your attention on the wrong things is infinite suffering.

The discipline of perspectival painting (perspectiva artificialis) beautifully illustrates the limitless power that comes from the proper expenditure of attention. Apart from the symbolism of perspectival painting in relation to focused attention, the birth of the discipline also opened windows of knowledge beyond what one might initially suppose. Samuel Edgerton argues that this mathematic principle alone made possible space exploration, the invention of the telescope, astrophysical sciences etc. He details the history of the practice, explaining that perspectival painting filtered from Euclid through the Muslim savant Alhacen (ca. 965 — ca. 1041) with his “Kaitab al-manazir or ‘Book of Optics,’ [which] became known as De aspectibus or De perspectiva in its Latinized editions” (22). The phrase came from the Latin “perspectus, participle of perspicere, meaning ‘to see through’” (22). The appearance of space comes as all lines constituting the picture converge at one singular point known as the vanishing point.

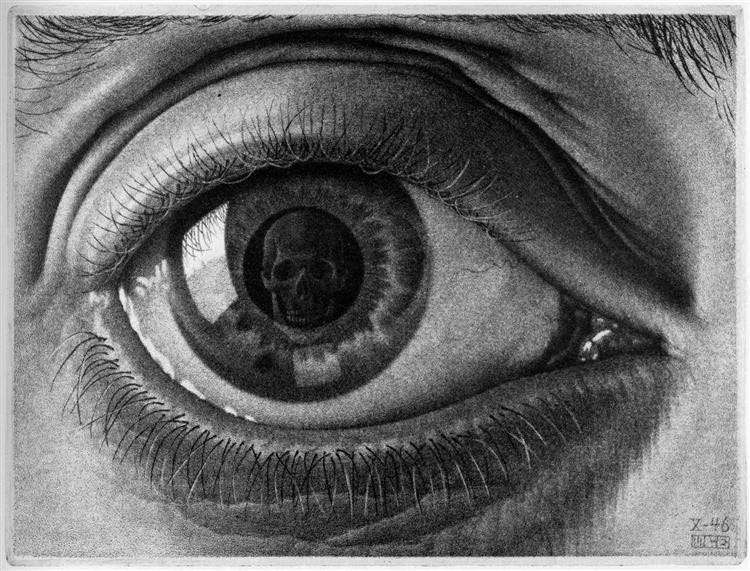

The vanishing point embodies a space of infinite regression, like a musical fugue, literally a place to see through because it forever remains out of reach. Were the beholder to physically enter the painting and approach the vanishing point, the converging lines (or the lines focused onto one point) would endlessly escape him or her. Matthew Ancell explains that “[by] definition, a point is not a place, and in real space these lines cannot intersect. The point thus represents infinity” (268, emphasis mine). As the artist, then, blueprints the structure of a painting according to linear perspective, he forges an infinity within the finitude of his frame. With every moment of the painting drawn, planned, and focused onto one specific point (for the effect of verisimilitude), he opens a window into the infinite — a place to see through, a place to see. This is the power of focused attention.

The visual element of this principle is certainly something we take for granted in today’s internet age of the pending metaverse and hyper-realistic video games. To see it properly, compare one image using perspective with another that does not. For example: the Libro de los juegos commissioned by Alfonso X (1283) contains several miniature pictures of games in al-Andalus (modern-day Spain) from the thirteenth century, including chess problems, backgammon matches etc.

Because the images are drawn without perspectiva artificialis, the board sits parallel to the picture surface, as if hanging on an imagined wall, with the players standing/sitting adjacent to the vertical board. Now compare these drawings to Masaccio’s “Holy Trinity” (1425–1427), wherein the great Renaissance painter first employed the techniques of perspective to make the crucified Christ appear (with depth of vision) as though he were literally there.

With the lines of the picture converging at one specific point (the feet of Christ), the painted plane opens up into a world beyond this world, allowing the beholder to look in and see, in some metaphysical sense, God. Thus, as the Renaissance masters spent their attention on crafting and searching for an infinite vanishing point, they found one both mathematical and metaphysical. Through the proper focus and expenditure of attention on their art — which was then focused onto one specific point — they found the infinite. In the focused use of their attention, they found God.

But beyond finding God (as if that wasn’t enough), many Western artists of the Renaissance felt that perspectiva artificialis also explained the very nature and mind of God himself. Edgerton writes that “theologians everywhere in Western Europe began to believe that the new geometric science of perspectiva not only provided the key to how God spreads his divine grace to mankind, but how he conceived the universe itself in his divine mind’s eye at Genesis” (29). Thus, the focused attention of God resulted in the construction and development of the universe in which we live. In this sense, God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son and expended the entirety of his attention to form the universe for us. Brunelleschi, who formalized the final mathematical theoretics for perspectival painting, thought this newly formed science granted “to mortal man the heretofore sacred privilege of imagining nature just as God himself projected it from his own divine eye” (Edgerton 76).

For the Renaissance masters, the proper expenditure of their attention opened windows to the Divine, to the Infinite, and etched their names into Western marble forever. This is the power of focused attention, or attention properly spent. Yet, despite the potential power our focused attention can wield, most of us spend it (almost exclusively) on the production of money. In today’s internet age of Bitcoin and world-wide inflation, everyone seems to spend their attention on building a monetary storehouse, or mathematically prophesying why Bitcoin will go to zero/infinity. We have gone from what Mircea Eliade called Homo religiosus to Homo sapiens, and now to Homo nummus, counting away our lives in whatever monetary denomination we feel most wealthy. But all this counting could ultimately result in a fourth nomination for the human race: Homo nihilis, as we count our way into obsolescence.

The importance of how you spend your attention cannot be overstated — for it is by means of your attention that you will accomplish anything in life, great or small. It is by means of attention (however active or passive) that you feed yourself, turn off your phone, help your son with math, or bring peace to your spouse. You and I, in our individual present tenses, are spending our attention on this essay (me in my now, writing something to help me think through an idea, and you in your now, reading in hopes of finding some useful information or entertainment). Of the functionally infinite things on which you could spend your attention (and the infinite abyss of the internet always calls) you are choosing to read this article — I thank you for that. Yet, as the Renaissance masters showed, there are many other (greater) things on which to spend your attention. By means of focused attention you can accomplish anything from saving someone’s life with a simple smile, to opening the portals of heaven and speaking with God (i.e., the Renaissance masters). Simone Weil wrote that the essence of prayer itself is attention, and that the “quality of the attention counts for much in the quality of the prayer. Warmth of heart cannot make up for it” (57). Thus, when you focus and expend your attention on the Divine, you can very literally pierce the veil of heaven and commune with God.

In today’s day, Big Tech will pay exorbitant amounts of money in exchange for your attention. What does that say? And, above all, for what price are you willing to sell the only thing that is truly yours? With every ticking hour, Lady Fortuna spins her wheel, and if you spend your attention on the right things, you can buy her favor. With the proper focus of attention you can buy a healthy relationship with your son, you can buy money, or you can know everything that happened to the Kardashians. But spend your focused, conscious attention on eternity, and you will find God.

If you liked this essay, subscribe here for more:

[1] Similarly, one can argue the same with regards to the Marxist model of labor as capital. Though connected to attention, labor is ultimately an ineffectual measure of capital. With labor, the true expense is not physical exertion, but rather your attention focused into learning specific movements of the body to generate some value or change. You never exactly “spend” your labor; once your labor is spent, you’re dead. What you spend, what slips away into the infinite black hole of time, is your attention, used to guide your labor to produce something meaningful/useful.

[2] While we (sometimes) rightfully reward those (with money) who most efficiently spend their attention in a not-so-free-market economy, we also wrongfully measure their value based on net worth. The former is the consequence of real value expended (attention), while the latter is a story sometimes inaccurately portraying the value spent.

Works Cited

Ancell, Matthew. “Perspectival Fig Leaves: The Failure of Representation in Calderón de la Barca’s El pintor de su deshonra.” Revista de Estudios Hispánicos, vol. 48, 2014, pp. 255–284.

Edgerton, Samuel Y. The Mirror, the Window, and the Telescope, How Renaissance Linear Perspective Changed Our Vision of the Universe. Cornell UP, 2009.

Weil, Simone. Waiting on God. Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2009.

Scott this is so profound! I’m impressed with your writing but also with your depth of thought and experience! I loved this principle. I’ve heard taught that the only thing that is truly ours is our agency and what we choose to do. I love how that is equally related to attention and how we spend our time. They are the same. Its wonderful to be encouraged to spend my time or attention and focus on God! Awesome, profound article! Thank you!!