To Become Again as a Little Child

An Easter Essay

I am certain, dear reader, that you have a memory quite like mine: a memory we hold on to, a memory as an ember of innocence burning still and buried deep, humming the reality that here we are, indeed, strangers from a more exalted sphere.

I was about five years old, Benny-the-Jet-obsessed, wardrobe and all. The evening summer sun glowed on our backyard as my father, my two sisters and I all played ball. I was the most impassioned and had the greatest stakes in losing. I knew quite well that a man certainly can’t play ball like a girl, let alone lose to two. The sun set and my father called (after what I now can see was great patience) for the last play. “Whoever wins this play wins the game.” I was at bat. I stepped up and swung—a clean hit, deep into the yard, and I ran. In the rapture I found myself at second base and closing in on third, my older sister breathing down my neck to tag me out. I ran close to third but missed it to juke her out and dive for home.

I look back in gratitude on the love of my family who cheered for that five-year-old me in cinematic splendor, but I never touched third base. They didn’t know, but I knew; and I knew, deep down, that if there was anything worse than losing to a girl, it was cheating to not lose to a girl. The memory replays strongest in my mind while in bed that night. I can still feel my little heart pounding. I don’t remember crying, though I cried. My dad must have heard me and came to ask what was wrong, or I called for him; I no longer remember. I told him I cheated, that I never touched third base, that my sisters were the real winners and I wept.

I marvel now, many years later, that such innocence was ever part of me, that somewhere deep inside of me—inside of each of us—is a child like this: one both meek and mild, sensitive to the whisperings of the Spirit and the light of Christ, with no “disposition to do evil, but to do good continually.” As a grown-up, my own conscience still beats to the same drum of moral law, but I must confess that the drumhead isn’t quite as tuned or taut, nor are the rhythms as strong as when I was a boy. When I sin, I do feel remorse, particularly as I feel the Spirit leave, but not to the same intensity as that summer night. In many regrettable ways, I’ve grown up and out of my boyhood innocence and quickness to repent. But my message to you (and to myself) is that this innocence we all once had is far from lost. That innocence and beauty found deep in the blurry frames of our memory is still latent within the bones of our hearts. In fact, that child-like meekness that we all remember is the essence of who we are (and who we always will be, even as grown-ups), and who we must become again.

In Matthew 18 the grown-ups of the New Testament (also known as the disciples) ask the Master of Meekness: “Who is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven?” Such a question certainly must have come from men and women thoroughly versed, either first or second-hand (as all true grown-ups are), in the ways of hierarchy, success, publications, degrees, bank balances, investments, achievement, and prestige. But the Master answers to none of that and called “a little child unto him and set him in the midst of them.” (As we read further, dear reader, please remember that you and I are, or at least we once were, that little child.) And Christ said unto his disciples “Verily I say unto you, Except ye be converted, and become as little children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven.” And then the answer: “Whosoever therefore shall humble himself as this little child, the same is greatest in the kingdom of heaven. And whoso shall receive one such little child in my name receiveth me.”

I assume that, like many of the Savior’s teachings, this thoroughly confused the disciples. How is it that a young boy, a child with no experience, with no understanding of the ways of men and of women, unqualified in every earthly sense, a creature of no achievement and no mastery, could stand highest in the kingdom of God?

The answer comes, at least in part, in a short story by Jorge Luis Borges. Near the end of his life, Borges wrote a fiction called “The Other” wherein the 75-year-old author encounters a younger version of his 15-year-old self against the laws of physics and reality. The two greet each other and come to terms with the fact that they are indeed the same man, though different across time and space (a narrative exploration of the philosophies of Heraclitus). In this fictional exchange, the older Borges remarks on this young man who he (Borges) is, but also isn’t, saying “I, who never have been a father, felt a wave of love for that poor young man who was dearer to me than a child of my own flesh and blood” (414).

When I read this story, I often think back to that little baseball-boy with his heart beating out of his chest in quiet childish guilt. Borges perfectly captured how I feel about him: poor little boy, how I love you. And in remembering him, I remember that he is me, and I am still him. The love comes as I realize that this guileless little boy resides within my soul forever—he is me. Borges’ fictional encounter with himself across time and space reminds the reader of the eternal encounters we have with our past lives and our past actions—daily encounters with who we have been, who we are, and who we are becoming. At all times we carry in our hearts the burdens of our wretched natures; but with those burdens we likewise carry the living memory of the pure and good children we once were, and, as Christ commands (and makes possible), who we must become again. In many ways, when Christ calls for his disciples to become as little children, His plea is not so much for us to change, but to return—to Him and from whence we come as we truly are, now having gained knowledge and experience. He calls for us to be one with Him and with that child we have always been, all through the infinite power of His atonement—a return to the child as the father of the man.

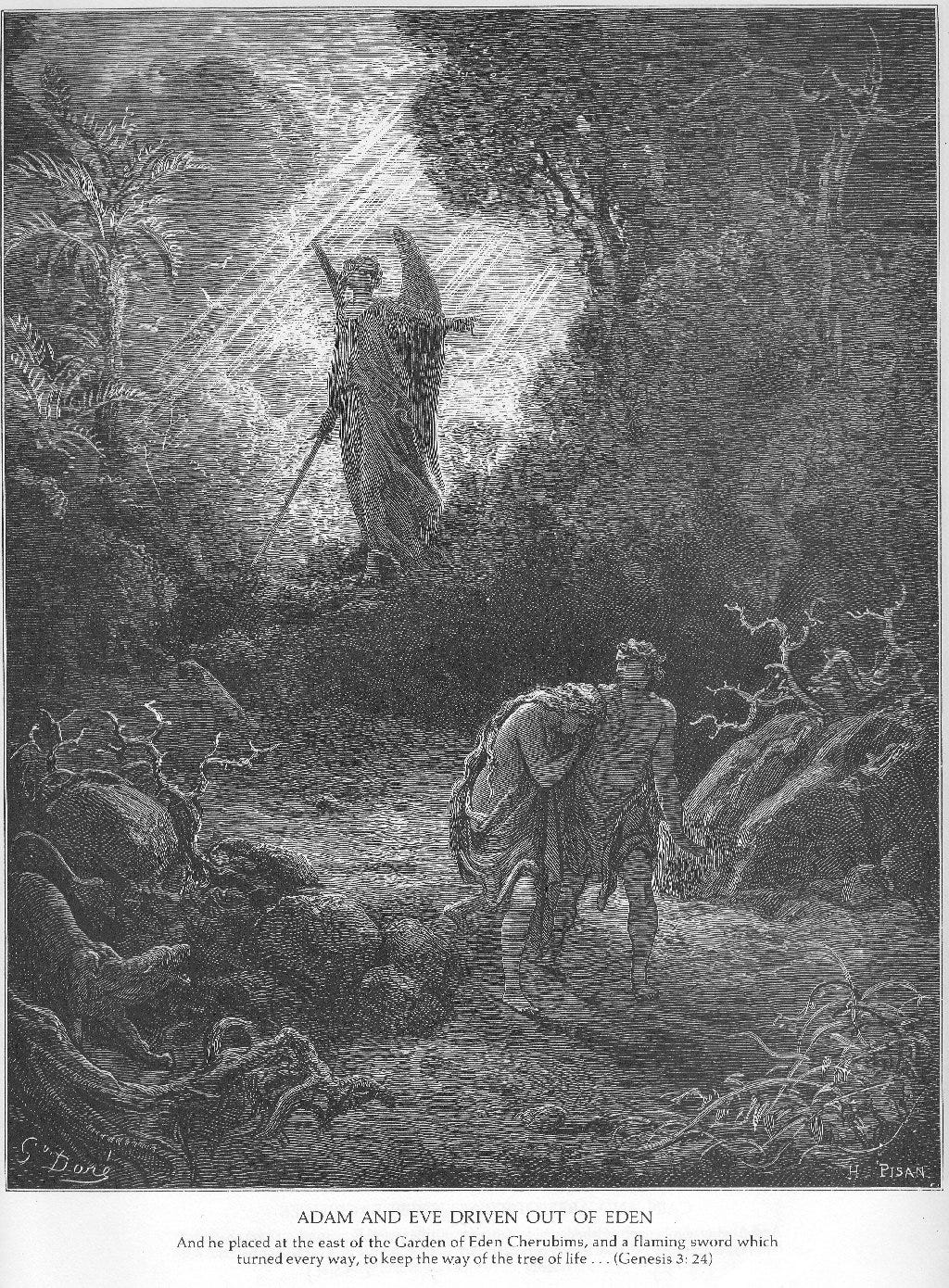

He calls for us to tie ourselves back to that innocence inherited from our life before this, and to that time when the veil was once thinner than we are to remember. When we return, and turn back to that child within, we receive Him. And in this restoration (a return ultimately to Him) we find love. But this restoration of who we are, through the atonement of Christ, becomes one of experience—as Adam and Eve now settled eastward of Eden. When we return to the tender innocence of our inner child, we return as a person worthy of the highest and noblest offices of Lord’s kingdom, now proven true and faithful by having chosen Him “as a child doth submit to his father.” We return to our innocence now free from our ignorance and can thus be saved; and by so doing we are no longer cast out but are gathered in as chickens under the wings of our eternal Hen.

The great and child-like (though far from childish) Truman G. Madsen wrote that sin “creates an antipathy to life, especially spiritual life. Then we stay away from the banquet because we have deeply betrayed the host. (Atheists don’t find God for the same reason thieves don’t find policemen.) We eat husks instead and then claim that the husks are the only food. It takes a little boy … to observe that, just as the emperor had no clothes, we have no food” (73). And such is the call of the Master to us all: come, and be as the little children; see, that you may feast and find rest.

That boyhood memory with my father resurfaces with greater frequency as I have children of my own. Now my children come to me in confessions and tears and the purity of their innocence; now I am the father, though I still feel as the son. When I look at their weeping eyes, I feel to sing a song of deep gratitude to have been born of goodly parents who cared and continue to care for me, and never mocked me for the celestial virtue once brightly resonant in my boyish heart. And I wonder at how it might ever be that I could give my children an equally goodly father. The answer, I suppose, resides within the child of my being, my pure and meek Borgesian “other,” whom I love. To give my children a goodly father I must turn back to that boy and become him again. I must harken unto the Father of my soul, and submit to Him, and become “meek, humble, patient, full of love, willing to submit to all things which the Lord seeth fit to inflict upon [me].” This Easter season, as you and I so do, and become again as little children, we will not only give our children the gift of goodly parents, but we will bring them, and, more importantly, the children of our souls, unto Him.